Help Needed After Tragic Brain Injury From BC Kickboxing Bout

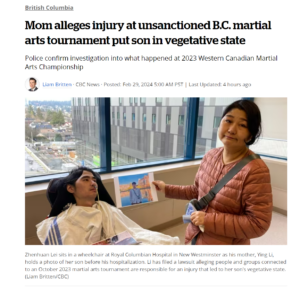

Zhenhuan Lei is likely in a permanent vegetative state. His mom, Ying Li, has been appointed his committee and commenced litigation.

Our firm is representing the family in this litigation and I will not comment publicly on the case.

That said I am happy the case has received media attention as Zhenhuan Lei’s medical needs are profound.

We have started a GoFundMe which already has been integral in providing assistance to the family and helped them cover part of the medical flight to bring Zhenhuan Lei back to China. That flight alone cost $100,000 of which Ying Li had to pay $30,000.

If you can donate to the fundraiser your assistance is greatly appreciated. If you can take a moment to share it that too is appreciated.

The GoFundMe can be found here.

_________________________________________

Update –

Ying Li has released the below public statement. I reproduce it here in full so you can hear from her directly and know this is who you have helped with your contributions. (please note this statement is from a week ago and he has since been successfully flown back to China).

Thank you everyone for all of your support. It is very much appreciated.

_____________________________

My son has been studying and living in Canada for five years. He is a cheerful, handsome, and kind young man who loves life. He diligently studies and works, often conducting experiments until late at night. He once told me that life only affords a few chances.

Suddenly, one morning, a news struck my family. In China, I received a call from a Canadian hospital informing me that my son was in a severe coma and needed surgery to avoid losing his life. Even with the surgery, there was no guarantee of saving him. They sought my decision on whether to proceed with the operation. Tearfully, I consented, desperately hoping for his survival. The surgery was successful, thanks to the exceptional skills of Canadian doctors, the meticulous care of the nurses, and his resilient vitality. He faced numerous dangers, overcame many obstacles, and reached his current state.

Ten days after the incident, with the assistance of the Chinese embassy and the Canadian immigration office, I arrived in Canada. It has been four months, and I feel as if I have experienced a death and am physically and mentally exhausted. I can’t comprehend how a well-behaved child, who participated in an entertainment competition, had his life changed so drastically. A promising life of a future scientist, an ambitious young man, has now turned into lying in a hospital bed every day and staring at the ceiling. I don’t know what he’s thinking, whether he harbors resentment, regrets, or frustration about participating in that life-altering competition.

After calming down, I must face all the problems that arose from this incident. My son grew up in a single-parent household, and he is my only child. All my efforts have been devoted to him, and raising him to this point has not been easy. Just as he was about to complete his Ph.D., hopes were shattered. Now, I have to embark on another journey, caring for him in the latter part of his life. Medical expenses, rehabilitation costs, family doctor fees, nursing expenses, transportation back to China, and more are looming in front of me. However, I don’t know how long I can accompany him. What will happen to him in the future, and who will take care of him? Unfortunately, amidst this misfortune, I am fortunate to have encountered a good lawyer named Erik Magraken, who has sincerely and significantly assisted me. I am deeply thankful for his help and the generous contributions from many kind-hearted people. My heart is full of gratitude.

Now, my concern is the treatment cost if he returns to China. Hiring someone costs 300 yuan per day, totaling 9,000 yuan per month. I don’t have that much money, so I can only take care of him myself. My own health is not good, and I don’t know how long I can care for him. I worry about what will happen if I’m not around, who will take care of him, and I am filled with daily anxiety and despair.

At this point, I just want to return to China as soon as possible for hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Perhaps it can help him regain some abilities. That is the most important thing, even if it’s just a slight improvement, such as being able to eat on his own. Watching him every day, I feel very sad. I am also reaching my limit. I want to go to the emergency room, but I am reluctant to spend money. I need to save money for his plane ticket to return to China for treatment, including hyperbaric oxygen therapy, skull repair surgery, stem cells, and more. Any treatment that might help him, such as acupuncture, massage, and traditional Chinese medicine, has shown benefits for him. So now, not only do I worry about his illness, but I also worry about money. Even if the plane fare is resolved, I still have to worry about the cost of treatment in China. It’s mentally and physically exhausting.